By Pooja Bhattacharjee

Capitalism is an economic system in which means of production are privately owned and the decisions with respect to production (what, how and when to produce) are largely determined by the forces of the free market that are largely based on profits.

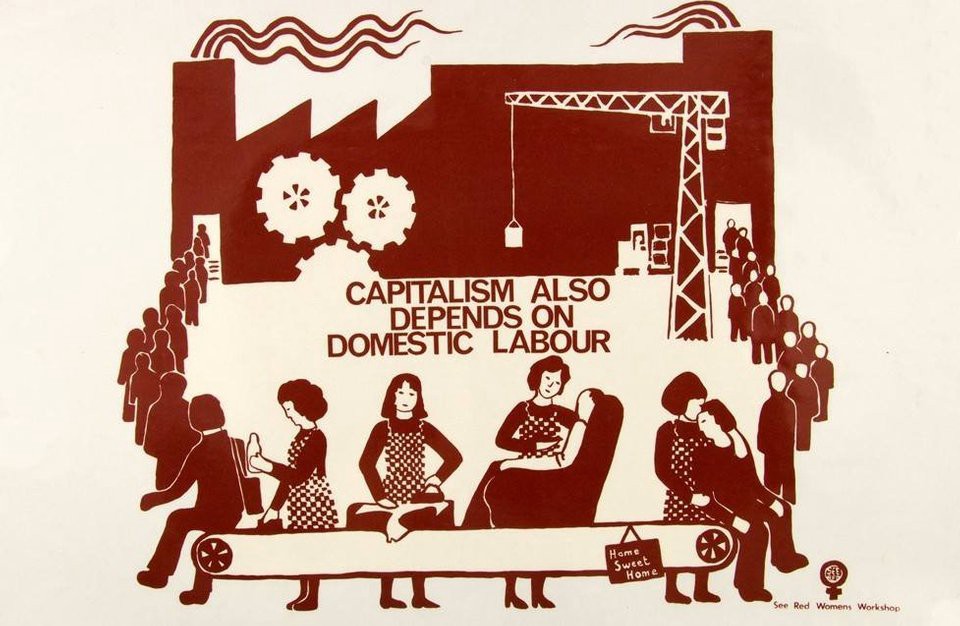

Capitalism structurally oppresses, restricts, and inhibits the access of marginalized individuals, minority communities, and differently abled persons by regulating the opportunities available to them. Based on such structures of inequities, it further exacerbates sexism, casteism, ableism, and racism. The commodification of women’s labour is at its peak, courtesy of the unequal power structures normalized by capitalism.

Feminism is a socio-economic and political ideology focused on dismantling gender discriminatory structures. It’s about fighting for and creating equality and a good life for everyone, regardless of their sex, gender, race, ethnicity, education, income, religion, or where they live. These goals cannot be achieved in capitalism. Using minority communities and individuals to generate economic and social value in service of reinforcing inequitable social stratification, race and social difference generate economic and social value for feminism when women are lauded for “overcoming” struggles based on gender, race, disability, and so on to fit themselves into a one-size-fits-all notion of feminist progress.

The focus for improving institutional sexism in the workplace is thus placed upon improving the gender pay gap. Solutions to alleviate the problem have been widely debated and disputed. Some argue that women should be remunerated for their ‘household chores’ (which would hardly serve to de-gender the concept of housework and thus maintains the sexist ideology that is associated with it); others say that working hours need to be more flexible to accommodate working mothers, while yet others argue men should simply help out more at home. Women on average do about twice as much housework as men. All of these arguments have their merits and de-merits but none of them really get to the crux of the issue. In order to be paid the same as men, we first have to fight the institutional sexism which exists at almost every level of society.

Many sectors such as automation, information technology and other outgrowths of capitalism are allowing women to compete and win in traditionally male-dominated fields. But observing that some women are quite empowered in capitalism does not imply that the path has been laid and that if we just follow it the goals of feminism will be reached.

Further, capitalism has set up a system of high working hours for low wages for its labourers and has established a pre-set power role between the owner of the factors of production and the individuals who sell their labour. Given the inherently oppressive and exploitative nature that capitalism entails, and the toxicity that is involved with it, the skewed power relation is only amplified when a woman is selling her labour for which she is paid a wage that significantly undermines the value of contribution made by her. The problems associated with capitalism is particularly biased towards women, there’s always some achievements or standards that they are not meeting, or a role model that capitalism strives them to be. This article achieves to streamline a discussion around the so-called role fulfilment mechanisms which we have become so adept at.

The Superwoman Effect

Superwoman – though a term associated with women empowerment and celebrates the achievements of women in corporate and on the domestic front, is often misused by capitalism and society to expect sacrifice from women. Gender, class and literature examines the superwoman phenomenon and the impact it has on the women and the stress level which is induced by capitalism. By definition, a superwoman is someone who, ‘takes on the roles of mother, nurturer and breadwinner out of economic and social necessity’.

The superwoman or supermom is associated with a woman who can juggle traditional role expectations associated with being a female and the role and expectations of career advancement and upward social mobility. In her book ‘The Second Stage’ (1981), Betty Friedan describes the superwoman expectation as the double enslavement of women by capitalism since it requires a sacrifice, either at home or work, to be a superwoman.

Girlboss Culture

Girlboss is similar to Superwoman, it provides an aspirational narrative to the struggles. While it is a good thing to work hard and have dreams and work towards achieving your dreams; the idea of social change projected by capitalism through Girlboss defines the narrow constraints of capital accumulation and its associated preservation of hierarchies and inequities. Girlboss feminism emerges from colonial legacies and structures of power that are predicated on maintaining inequalities based on race, ability and normative gender expression.

Success is the headliner of girlboss feminism. ‘The Girlboss Platform’, started in 2016, represents the cultural shift toward marketing personality as a component of successful capitalist subjectivities. It uses motivational content by merging personal and professional upgrades to attain success, the personal becomes a vital selling point in girlboss culture. A pattern of desirable personality traits emerges through the platform’s user engagement, highlighting the role of collective intelligence in shaping conceptions of the ideal empowered woman.

Through these ideas of superwoman and girlboss, capitalism is selling this narrative claiming that anyone can attain wealth, regardless of gender, race, ability and so on – so long as you work hard, think positively and rise above any obstacles thrown at you. By leveraging mediated spaces to perpetuate such aspirational narratives, girlboss feminism naturalizes and obscures the conditions of severe inequality endemic to capitalism.

In her analysis of beauty and lifestyle bloggers, Brooke Erin Duffy highlights the role of authenticity in capitalism. Duffy notes that authenticity represents the demands for self-promotion created by emotional capitalism, defined by Eva Illouz as ‘the complicated intersections of intimacy and political/economic models of exchange’. Girlboss users respond to emotional capitalism’s norms of engaging what is personal and intimate as modes of profitability. This profitability centres on reinforcing gendered expectations of women’s capacity for expressing vulnerability, pointing to how emotional capitalism operates through structures of gender essentialism. Women are expected to be vulnerable and emotional capitalism engages this norm as an opportunity for extracting value. Through the repetitive selling of their own relatability and authenticity, Girlboss users structure the marketing of personality traits as a key feature of gaining influence.

Lastly, to overcome sexism it is necessary to combat this system as a whole, rather than focusing specific issues. The whole system must be critiqued and examined. The incredible technological and scientific advances of the past forty years could have been channelled toward dramatically reducing poverty, improving health care outcomes and the ecological sustainability of our production processes and ensuring security in the supply and distribution of clean water, nutritious food, and adequate housing. These are things that all people value. These are also things that would greatly empower women who suffer disproportionately from the lack of these things.