Kolam, alpana, muggu, or chowkpurana – this art form has historically been the domain of women.

Boasting of India’s long-held tradition and culture, these intricate patterns sitting gracefully on the floor of almost every other Indian household allude to an art form that has essentially been the domain of women. Traditionally passed down through generations, the women of India have kept the art of rangoli alive. Although creating rangolis is a still a daily practice in certain rural areas of India, in cities, rangolis are now often limited to auspicious days and festivals such as Diwali, Lakshmi Puja, Gudi Padwa, and Onam among others. However, a little research into the herstory of rangolis makes it clear that the significance of this art form goes much beyond being auspicious, aesthetically pleasing, and decorative. To know more about the significance of this art form and its connection to women, read on.

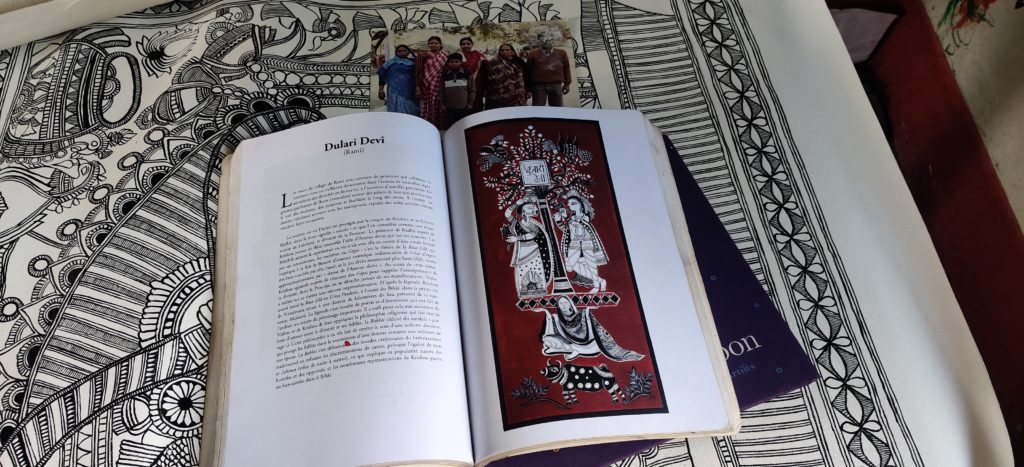

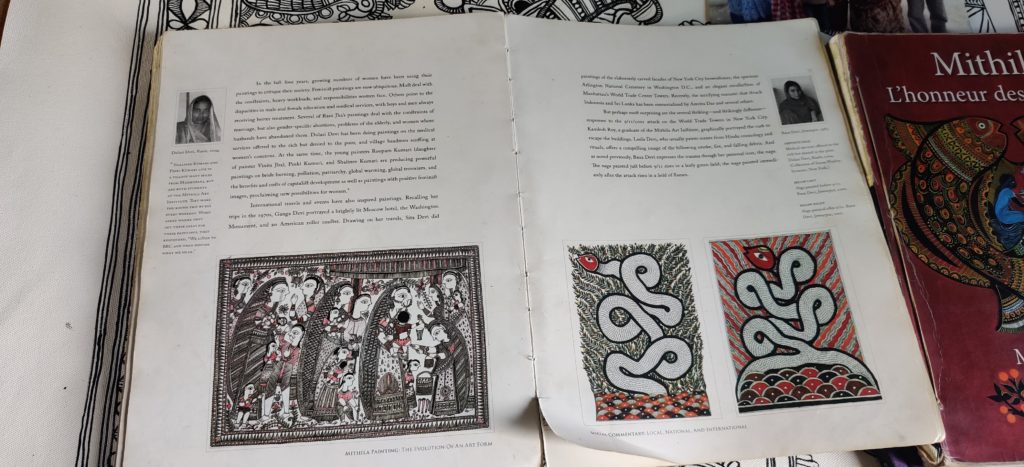

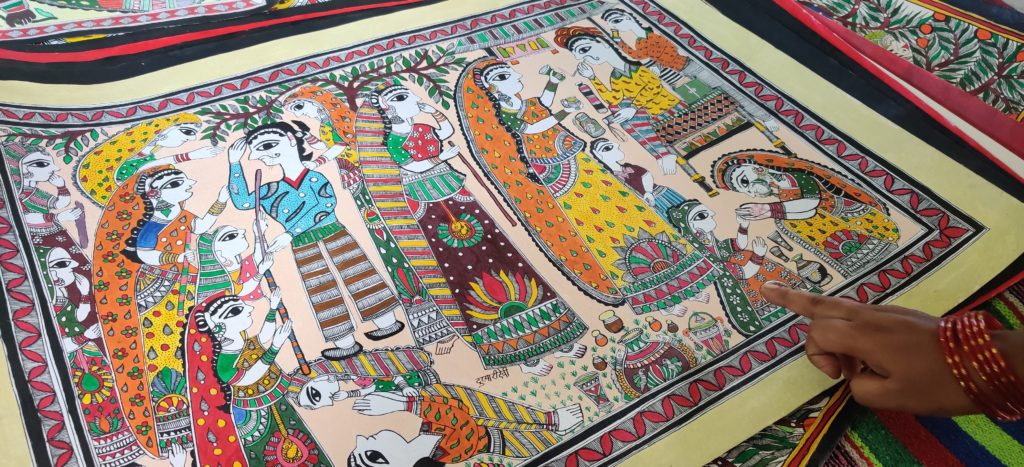

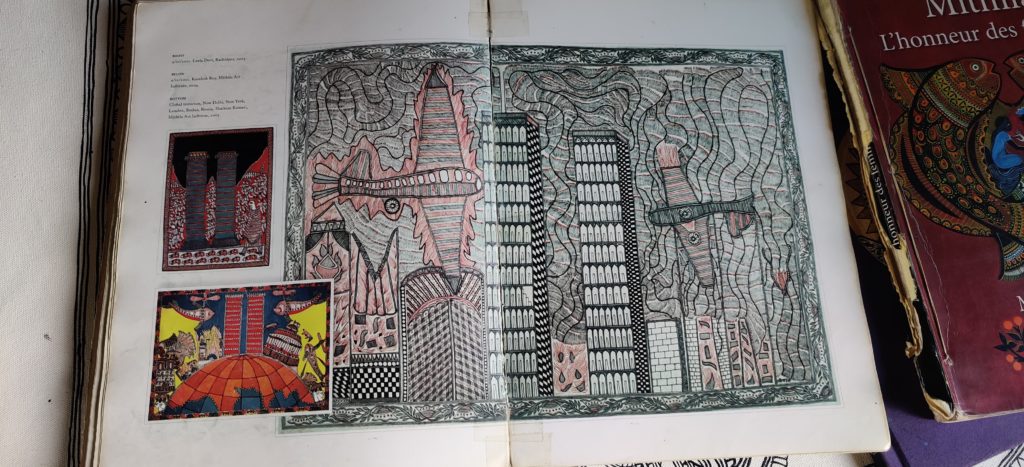

Diversity of Rangolis across the States of India

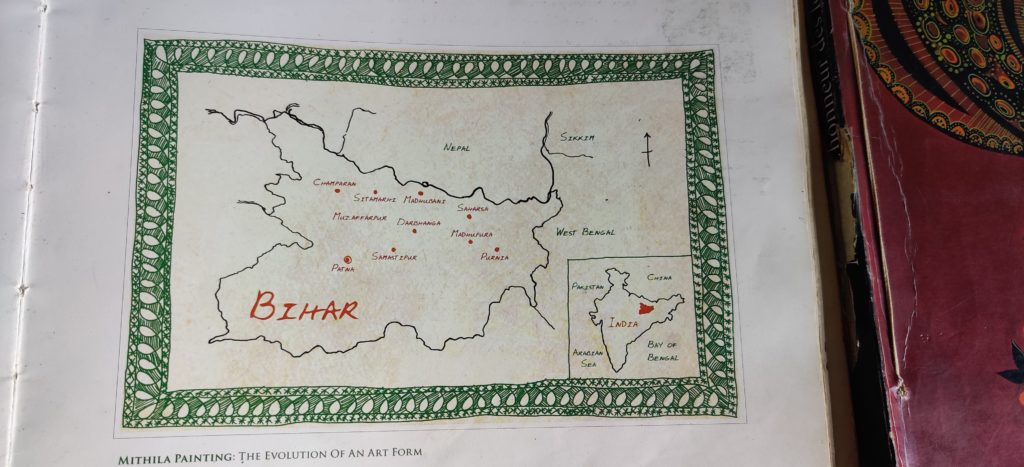

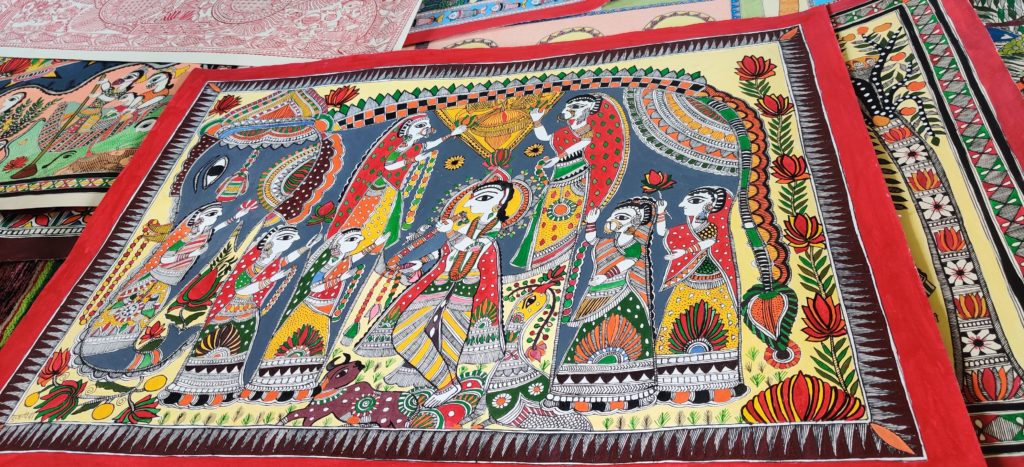

This art takes varied forms in different parts of the country – mandana in Rajasthan; chowkpurana in Uttar Pradesh; aipanaa in Uttaranchal; aripan in Bihar, muggu in Andhra Pradesh; alpana in Bengal; jhoti, chita, and mujura in Odisha; rangoli in Gujarat and Maharashtra; and kolam in Southern India, mainly Kerala and Tamil Nadu. While modern feminists are striving to make visible women’s presence and potential in various male dominated disciplines today, there are and always have been areas that are exclusively the domain of women. Sadly, these areas often ignored, overlooked or dismissed, perhaps because they aren’t viewed as being challenging or important enough, which again is a testament to the ever-prevailing biased view of gender in our society. Rangoli is one such art form that requires patience, practice, and persistence, in addition to fine judgement, visual-spatial intellect, mathematical precision, and the ability to concentrate for hours altogether.

Significance of Rangoli and Connection with Women

Since ancient times, women have been waking up in the wee hours of the morning to clean the thresholds of their homes and create rangoli patterns, which are believed to invoke God’s blessings and ward off evil. In Southern India, this ritual is believed to bring divine grace and cosmic energy to the household, and is performed by the matriarch of the household, the “grand priestess.” The ‘kolam’ is drawn as a prayer in illustration, inviting the goddess of prosperity, Lakshmi, to bless the household. Writer and multimedia journalist, Rohini Chaki, observes that the very act of making of the kolam is a “performance of supplication.” The artist bends at the waist and stoops to the ground as she works on her kolam with bare hands, without the use of any tools. Drawing the kolams with bare fingers in a form of Mudra technique that is believed to boost the spiritual stamina of women. Kolam is a form of a prayer, meditation and expression of the sacredness of life.

Kolam and Rangoli, Porselvi writes, are also alternate forms of communication for women. The various symbols and motifs presented in kolams and rangolis are a starting point for understanding this alternate form of discourse. Further, mythologist and author, Devdutt Pattanaik notes that the kolam almost serves as the message board of the household. A casual look at the daily patterns could help in determining the mood of the household. “Beautiful patterns indicated joy. Elaborate patterns indicated focus and dedication. Shoddy patterns indicated a poor disposition, some unease. Absence of a pattern meant something was amiss in the household.” The kolams also demonstrated the presence of a woman householder, and that the household is in the state of overflowing abundance and not in misery. Rangoli is also drawn to indicate that the lady of the house is ready to receive visitors. The rangoli is wiped off each morning, reminding that things change. With family’s growth and prosperity, the patterns become more confident and joyful. However, during festivals, women had to set their creativity aside, and adhere to the fixed patterns demanded by cultural traditions. At such times, women became a part of a larger community – the village rules became the household rules. Vijaya Nagarajan, an Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Theology/Religious Studies and the Program of Environmental Studies at the University of San Francisco, writes in her book Feeding a Thousand Souls: Women, Ritual and Ecology in India, “The kolam is a powerful vehicle for Tamil women’s self-expression, a central metaphor and symbol for creativity.” Talking about the connection of women to this ritual, she writes, “It evokes an entire way of being in this world; it articulates desires, concerns, sensibilities, and suffering, and ultimately it affirms the power of women’s blessings to create a desired reality: a healthy, happy household.”

Rangoli Symbolism & Spiritual Significance: Patterns, Colour, and Symmetry

Spiritual gurus believe that rangolis are a science of creating energy, and thus, the design, symbols, lines and colours, all play an important role.

In Odisha, intricate designs made from rice paste, called jhoti or chita are drawn not only for decorating the houses, but also to establish a relationship between the mystical and the material, and thus are highly symbolic and meaningful. At different occasions throughout the year, women perform several rituals for the fulfilment of their desires. For each occasion, there is a special motif drawn on the wall or on the floor.

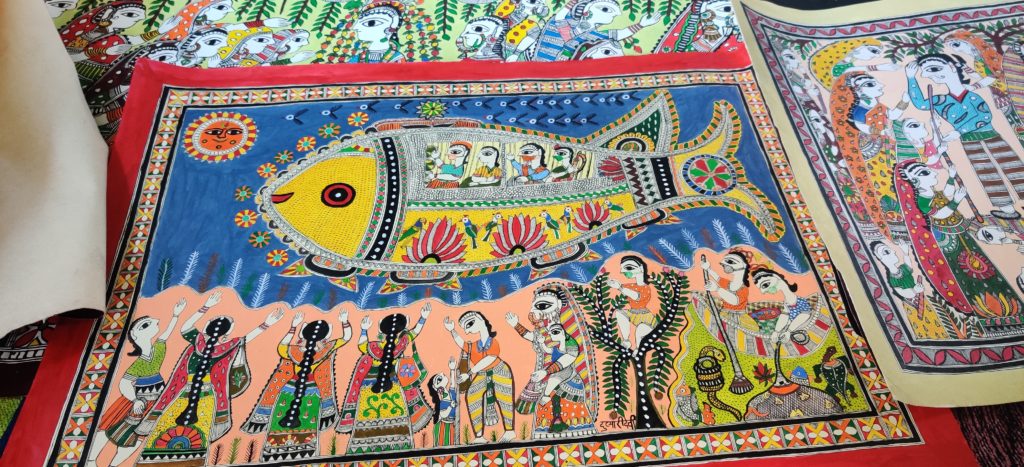

Art historian Nayana Tadvalkar writes, “The art of rangoli is a storehouse of symbols.” As such, a rangoli is incomplete without the expression of rich symbolic language. “Beginning with the auspicious dot, the symbols go on expanding to form a line and the basic geometrical shapes like the circle, triangle, square and so on, each having its own significance,” Tadvalkar elaborates. Indian women create rangoli designs in auspicious geometric shapes, flower patterns, and images of gods and goddesses. Rangolis are also often drawn as a prayer for prosperity, fertility, and good health. Animal motifs are frequently drawn in rangolis all over India and have several beliefs associated with them. The naga (or cobra) is believed to bestow all the boons of earthly happiness – abundance of crops and cattle, prosperity, offspring, health and long life on mankind. As women draw nagas in their rangoli, they invoke their blessings of prosperity and fertility and to ward off any evil. Due to the ability of the nagas to replace their old skin with new, they are respected as symbols of change, renewal and regeneration and are worshipped for progeny, prosperity, and health. The fish is a common motif drawn in rangoli all over India, finding special prominence in the alpanas of Bengal and the rangolis of Parsis. It is regarded as a symbol of fertility, abundance, conjugal happiness, providence and a charm against the evil eye. Purna kumbha is an ancient Hindu symbol representing the pregnant mother goddess, a deity worshipped as a harbinger of good fortune and fertility. In alpana patterns, creeper patterns are referred to as vansha-vel, i.e. creepers of progeny of heir, symbolising continuity of family lineage. Tadvalkar observes, “The understanding and interpretation of […] symbolism leads to the conclusion that these motifs were employed in this ancient art of rangoli to denote an indirect or figurative representation of a significant idea, conflict, or wish.” These symbols of fertility, procreation or the cosmic life force and regeneration are in one way or the other ‘symbols of life,’ and thus highly auspicious.

Quick fact: Fertility goddesses and auspicious geometric designs appear in the Indus Civilization (ca. 3000 BCE).

While we are naturally drawn to symmetry owing to the laws of visual aesthetics (our brain is hard-wired for symmetry), symmetry in rangolis has much greater significance. The symmetry of the rangoli holds critical importance in channelizing of energy levels into the house and enhancing positive energy. The higher and sharper the energy level is desired, the sharper is the design of the rangoli. However, most rangolis are in circular form, which helps to bring down energy levels in the house, promoting calmness and contentedness. Especially if the rangoli is made for Diwali or such auspicious occasions, it had to have that spiritual angle to create energy centers, which can have positive impact on people. “The pools of energy created by specific patterns of rangoli motivate and channelize positive energy in people.” Moreover, symmetrical patterns are seen as a symbol of wealth, happiness and growth in all religious across the world.

Research has suggested that the geometric patterns and colours stimulate the brain and impact neural circuitry and emotions in a manner that has a calming effect on the person who views it. The importance of this art is embedded in the science of vibration patterns. Thus, with the change of colour, design and form, the vibration of a rangoli changes.

Kolam is also a metaphor for coexistence with nature. While modern Indian women use chalk or powdered colour to make these patterns, philosopher and author, Peter Raine, notes that traditionally, these rangolis were made of coloured sugar in order to feed the ants, who were believed to be reincarnated Gods. Nagarajan, in her book, refers to the belief in Hindu mythology that Hindus have a “karmic obligation” to “feed a thousand souls,” or offer food to those that live among us. By providing a meal of rice flour to bugs, ants, and insects, the Hindu householder begins the day with a “ritual of generosity,” with a dual offering to divinity and to nature (as cited in Chaki).

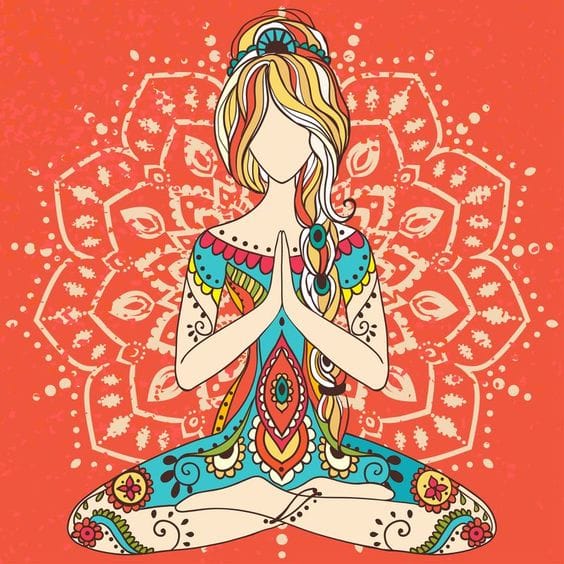

The myths, stories, and traditions surrounding the art of rangoli remind us of the special connections between women and the Mother Earth; the woman-nature association. The kolam of Southern India and aripan of Bihar are also made as an offering or thanksgiving to the earth goddess. As mentioned earlier, Porselvi points out that the identification of the unique motifs found in rangolis becomes the starting point in understanding the Mother Earth discourse. Motifs are a unique feature in women’s art forms, and women’s thought processes are characterized by multiplicity and diversity, as identified in their rangolis. Moreover, Porselvi asserts that the worldview of women is the worldview of abundance. Ecofeminist and environmental activist Vandana Shiva describes, “A worldview of abundance is the worldview of women in India who leave food for ants on their doorstep, even as they create the most beautiful art in kolam, mandalas, and rangoli with rice floor…”

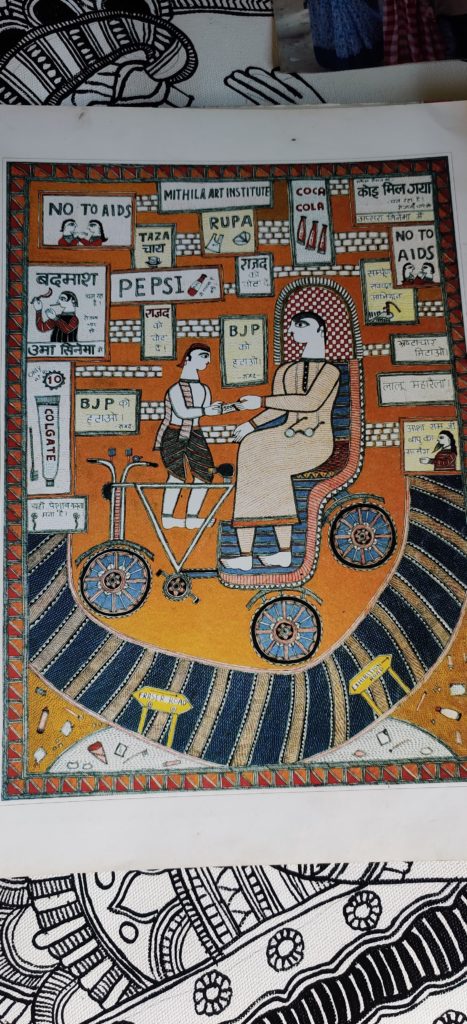

In deep and unique ways, the art of rangoli reaffirms the notion of the role of women as the “protector” of the household and “nurturer” of the universe. While a few feminists would be critical of this view, I take pride in this unique, respectable, and worthy status carried by women over centuries. Over the years, rangolis have also transitioned into a tool for social awareness on a range of social concerns such as female feticide, rape, environmental imbalances, “education for all,” secularism, and women empowerment.

The history and culture of rangoli can be traced back to at least 7000 years, with rangoli finding mention even in the great Hindu epics of Ramayana and Mahabharata. Indian women need to be lauded for carrying this unique tradition and art form across India and the globe, for centuries, passing it on from one generation to another.

If you’re a visual learner, you might enjoy this piece on “Rangoli for Diwali: Discover rangoli styles from different parts of India” on Google Arts & Culture. Have a look: https://artsandculture.google.com/story/rangoli-for-diwali/sQWxwh-VUtKR3A?hl=en