Authors: Mitali Nikore, Khyati Bhatnagar, Priyal Mundhra

Research assistance: Ishita Upadhyay, Girish Sharma, Shruti Jha

India’s growing economy needs 103 million skilled workers between 2017-2022. Yet, over 100 million Indian youth (15-29 years) are not in education, employment or training (NEET), of which around 88.5 million are young women. The proportion of working-age women receiving any form of vocational training over the past decade has been increasing from 6.8% in 2011-12 to 6.9% in 2018-19, vs. an increase from 14.6% to 15.7% for men.

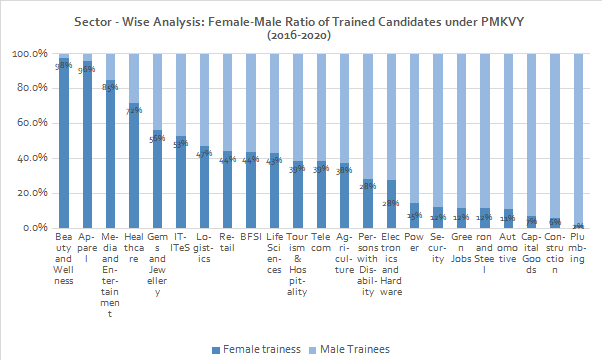

Furthermore, there is a concentration of women trainees in non-engineering, labour-intensive sectors and job roles. Under the flagship Prime Minister Kaushal Vikas Yojana (PMKVY) for short-term skilling, although women comprised 49.9% of enrolled candidates over 2016-2020, they remained concentrated in traditional, “feminised” sectors such as beauty, apparel and healthcare, and almost entirely excluded from high technology or more mechanised sectors. Between 2014-19, women comprised 17% of enrolment at Industrial Training Institutes (ITI). Women formed only 4.3% of enrollments in engineering trades vs 54.7% in non- engineering trades.

Source: NSDC Analysis, June 2020

In this context, prolonged closures of education and skilling facilities during the COVID-19 pandemic are creating new barriers, especially for young women trying to enter the labour force. Between September 2020 to May 2021, Nikore Associates undertook consultations with over 60 stakeholders belonging to community-based organisations (CBOs), academic institutions, government agencies, women-led self-help groups (SHGs), and corporates to understand these barriers.

1. Gender-based digital divide: During COVID-19, several CBOs switched to online and Whatsapp-based skill training modules. However, in 2020, 25% of India’s adult female population owned a smartphone vs. 41% of men. Consultations showed that owing to lower ownership of smartphones, unfamiliarity with phone features, high data costs, and lower priority being accorded to women’s skill training, several women and adolescent girls dropped out of training. In one example of this, a Mumbai based NGO shared that large family sizes necessitated phone-sharing. Coupled with financial constraints which limited the purchase of internet packages, women’s enrolment in their online skill training courses had fallen.

2. Unpaid work: Indian women were already spending an average of 5 hours per day on unpaid care work, vs. 30 minutes spent by men pre-COVID-19. Nearly 45% of women’s unpaid work is centered around childcare, and the unavailability of creche facilities at skill centers deters women with caregiving responsibilities from joining. Consultations across social groups revealed that the presence of male relatives and children at home due to closure of workplaces and schools led to an increase in care work. For instance, an SHG mobiliser in Telangana shared that the women in her community were unable to attend trainings and SHG meetings owing to domestic work.

3. Commuting options and mobility restrictions: Even before COVID-19, 28.3% of women enrolled in ITIs cited difficulty in commuting as their reason for withdrawing from skill training. Lockdown measures disrupted public transport services, increased the risk of gendered violence in empty public spaces, and heightened mobility restrictions for women. For instance, a Manipur-based CBO shared that even after lockdowns eased and training centers re-opened, women were unable to re-join trainings as they did not have a means to commute.

4. Social norms. In a pre-COVID-19 survey, 58% of female trainees cited marriage, 21% cited family issues, and another 7.5% cited family perception of ITIs being more suited for males as major reasons dropping out of skill training programs. Consultations show that with COVID-19, families have become even more reluctant to allow young women to step out for training. For instance, a Delhi-based CBO conducting training for women to take up cab-driving saw much higher resistance from families post COVID-19.

5. Wage gaps and low likelihood of employment post training: Even after training, women’s likelihood of obtaining a job was lower than men. About 46.9% of women who received formal vocational training did not enter the labour force, vs. 12.7% of men (NSSO 2019). An analysis of data from 64 ITIs shows that only 25.6% of female trainees received job offers in 2018-19. In a survey of employers, 50% of MSMEs and 32% of large companies expressed a reluctance to employ women owing to the need to ensuring their security, risks with involving them in heavy manual labour, and their interest in working in closer proximity to their homes. Women also suffer gendered wage gaps. Between 1993-2018, the average wages for female casual workers in urban settings stood at ~63% of the male wage. Consultations showed that during COVID-19, these gender-biases could worsen, especially across small businesses owing to repeated macroeconomic shocks and working capital constraints.

The Government of India (GOI) has recognized women as a priority group under the Skill India Mission. Further, the GOI’s recent announcement to conduct a tracer study to gauge the impact of PMKVY on female labour force participation is a much-needed intervention to understand the correlation between skill development and employability for women.

As the country moves on to a medium-term path of economic recovery post-COVID19, several additional measures can be considered by the GOI to encourage government and private training providers to undertake gender-inclusive skilling interventions.

The GOI could formulate an incentives-based approach with gender targets for all courses under its National Skill Qualification Framework (NSQF). Reward mechanisms can be created such that training partners become eligible for additional financial support if new modules are devised for women’s training, or if there is an increase in enrolment and placement of female candidates, especially in non-traditional trades.

A composite national and state level ranking of skilling institutes should be devised to assess gender mainstreaming efforts, including increasing awareness, recruiting female faculty and offering counselling services for female candidates and potential employers.

There is also an urgent need to create gender sensitive infrastructure at skill training institutions, with procurement standards of private training partners under government schemes mandating separate washrooms, strict security, balanced gender ratio of trainers and the provision of safe transport. Gender sensitive infrastructure should be standardized across all government and private skilling institutes.

A host of long-term structural barriers, such as occupational segregation, the income effect of rising household-incomes, and increased mechanization, which when combined with increased unpaid work, growing gender disparities in education, and heightened mobility restrictions due to the pandemic, have intensified the challenges of bringing women back to work. Thus, bridging the gender gaps in skill training and making women ready for a digitized, technology-driven post-COVID-19 workplace, should be a priority for GOI.