Arthita Banerjee

New Wave is essentially an art word that came to be defined by the French trailblazing directors who exploded in the film scene in the late 1950s. These young directors reshaped the cinematic narrative by rejecting the traditional linear fashion of storytelling and ultimately creating a whole new language of film. The movement had a vibrant influence on international cinema and it might just be responsible for bringing out the Kazakh film industry from obscurity to that of critical acclaim.

It might be interesting to look at the history of Soviet Russia and understand how Lenin was instrumental in bolstering the ‘Bolshevik Cinema’. According to the Bolshevik government’s first Commissar for Education, Anatoly Lunacharsky, Lenin remarked that, ‘Film for us is the most important of the arts’. He understood early on that possibilities of cinema as a means for propaganda, agitational and educational tool and went on to nationalize the film industry exercising complete control over the productions.

Moreover, Lenin and other Bolshevik leaders looked on the motion-picture medium as a means of unifying the huge, disparate nation. The young Soviet Union was faced with a large population made up of many nations and ethnicities. To top it off, most people were illiterate and the means of communication in the country was largely undeveloped. The Bolshevik leaders also faced the daunting task of explaining the revolution to the people. Therefore, the promise of the medium of film – although only a silent medium, at the time, held endless possibilities.

Post the revolution, Moscow exercised tremendous control over all of its Soviet citizens we’ll try and trace the complex history of Kazakhstani culture in a time when communism was permeating through the fabric of their native culture. In the late 20s the west and the rest of the world were on a steady diet of all American, Cowboy ‘Westerns’. It is interesting to note that during the same period the Kazakh filmmakers came up with their own brand of ‘Easterns’. It gloriously chronicled fights between The Red Army against the Basmachis, who are the Kazakh nomads and essentially were anti-communist units interested in the Old Islamic Order.

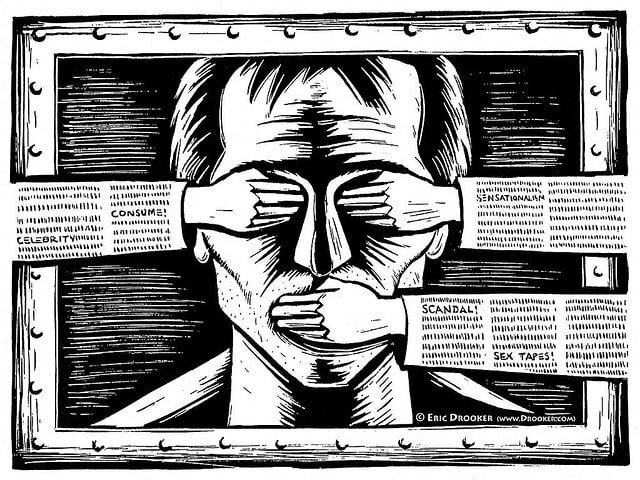

The films from that period were considered so scandalous in nature to the communist regime that when they were finally re-released 10, 20, even 30 years later the dialogues were completely redacted to the point of complete mutilation. Evgeny Lumpov, a documentary filmmaker, despite investing his personal fortune to the tunes of thousands, could not retrieve the original copy of ‘It happened in Shubla’, an iconic work of Kazakh Cinema.

In a limited amount of time, Kazakhstan managed to build its own cinematic world which was quite distinct from Uzbekistan, Georgia or Russia. The dominant component of their universe was a constant civilizational tension between the city and the countryside, Kazakh customs and Russian traditions. Kazakhstani cinematography is also worth paying attention to. The great camera men such as Akshat Ashrapov and Mikhail Aranyashev were responsible for creating the distinct visual peculiarities.

The Kazakh New Wave was a reaction to the very harsh and authoritarian censorship of the Soviet order. All artists were being railroaded into working within ideological guidelines and sometimes the whims of the State officials. Russian was the primary choice of language in most Kazakh films but The Needle was the first film to take the route of exploring the native language. The film was a thriller about a young man’s fight against the local drug Mafia, directed by Rachid Nugmanov. In a still, we witness a village elder trying to speak with the protagonist in native Kazakh but both of them fail to understand one another. The scene is an attempt at depicting the severed cultural connection between the country’s culture and its people. The film was rereleased in 2010 as Needle Remix with several additional scenes that had been previously cut from the film.

The renowned Kazakh director, Abai Karpykov’s film, The Little Fish in Love tries to portray the harsh realities of urban life in the USSR. The film mainly tracks down the wanderings of an aimless young man through an unnamed Kazakh city. There is an element of resilience to any kind of art that is made under circumstances of repression and the metaphorical qualities of the directors then reflect in the art work, which on the contrary can’t be said at a point blank.

Despite being in the thick of the regime, freedom did exist and the filmmakers were for the first time detailing out the societal problems through the medium. The movement was not an accidental explosion. Yermek Shinarbaev’s “Revenge,” is also a favorite among many cinephiles. The critics describe it as “violence versus the life of art and peace.”

Darezhan Omirbaev might be one of the few remaining directors from the New Wave era who is still working. Kazakh new wave burned out pretty quickly after exploding into the international scene. The movement breathed its last by the time the country gained its independence in 1991 and the Soviet collapsed. Though, there is no denying that the cinema of the region evolved owing to the paradigm established by the New Wave.

From early Soviet censorship days, to now exploring gender norms, immigration issues, and the brain drain that Russia is experiencing, the Kazakh Cinema has indeed come a long way. Aushakimova’s groundbreaking film, ‘Welcome to the USA’ follows 36-year-old woman – Aliya’s journey, who has just won the US Diversity Visa lottery, as she gets her affairs into order and prepares to immigrate. The film was named the Best International feature at New York’s NewFest LGBTQ Film Festival. It makes astute observations about feeling foreign in your own country.