By Avani Bansal

(With RSS pushing the wall, with installment of Bharat Mata statue at RSS office, in Bareilly, UP, as latest as yesterday, it is now anyone’s guess, what a Bharat Mata holding a saffron flag is meant to depict – Hindu Nationalism – an idea that works for the RSS and BJP but an idea that is simply against the idea of the Constitution and the idea of India that emanates from it. So we need to think deeply of what we mean by ‘Bharat Mata’)

The Constitution of India doesn’t provide for a gender for ‘Bharat’. The very first Article of the Indian Constitution states that ‘India, that is Bharat, shall be a Union of States’ (Article 1). So why not let ‘Bharat’, just be ‘Bharat’, one which as per the Preamble – we, the people of India (‘all’ the people of India), have given to ‘ourselves’? Why add the suffix ‘Mata’, and does this add any value to our understanding or how we relate to our Nation?

Now this idea of seeing one’s nation either as a patriarchal or a matriachal figure is not uncommon and varies from country to country and time to time. Why is Germany – a father figure, requiring a male pronoun and why is United Kingdom – a ‘she’, is difficult to answer with some solid logic except by looking into the culture and political/historical milieu of every nation, and ofcourse some history. While gender neutral terms do exist – ‘homeland’ or ‘ancient land’, there are also some countries who don’t use any of these suffixes, oddly referred to as ‘orphans’ (vehemently oppose that term!), here :

https://www.mcislanguages.com/fatherland-vs-motherland-what-is-the-gender-of-your-country/

(Map from here)

How India came to be called ‘Bharat Mata is an interesting story in itself. But before coming to that – why does this question matter?

I will argue that merely using the word ‘Mata’ without thinking of deeper questions, does us a disservice. Here’s how :

First, the logic that ours is a land where women are worshipped as Goddesses has done precious little in actually increasing the collective respect that we accord to women in our society and in our country. As the title of the movie ‘Matrabhoomi – a nation without women’ shows on every possible gender matrix, India’s performance is worth hanging one’s head in shame. With the increasing crime rate against women, scant attention on women’s reproductive health, education of school girls, women’s safety and most importantly women’s represenation in public offices including politics, shows that women are far from being ‘worshipped’ in India. As in ‘Pratima Visarjan’, the famous painting by Gaganendranath Tagore, we think of women, like Goddesses, on specified days and then go on to submerge them in the rivers and in our active memories, making peace with everyday injustice against those most close to us.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pratima_Visarjan_by_Gaganendranath_Tagore.png

Secondly, this particular form of love for ‘mother’ has been well adorned and subjected to poetry, literature, essays, books amongst others, not just in India but around the world. In India, a mother’s love has reached the epitome of love’s expression with mothers cooking for their sons, until they can no longer cook and ‘mamma’s boy’ being taken as a badge of honour than showing lack of independence. The close familial ties in India means that the expression ‘mata’ or ‘mother’ can be naturally extended to the nation-state, with seemingly little or no objection from anyone and common rejoice in the emotional warcry of ‘living and dying for mother and motherland’. But here’s the challenge.

While we exalt the love of the mother, why do we have such trouble accepting ‘Bharat’ as just a woman – and by the same analogy, her in different roles – of a lover, a sexual being, a single woman, amongst others? What, for instance, explains the controversy around M.F. Hussain’s famous painting the ‘Bharat Mata’?

https://www.skyshot.in/post/7-greatest-indian-painters-of-all-time

Thirdly, if the idea of India is all inclusive, as per our Constitution, then exalting ‘Bharat’ as a Mother may in some way exclude people belonging to other religions who may not see the concept of nation tied to that of a mother or a father.

But then, if Jews have a fatherland, Russians have a motherland, why can’t we have a motherland? Because, we have never aped anyone. India is an experiment – one to design a unique solutions to all of its unique problems. Differences existed even when our Constitution was being drafted, with members belonging to extreme right and left wing, including moderates, trying to shape the India of their dreams. But it is the idea, as prescribed in the Indian Constitution, that won the day, and for our purposes has to be the milestone, from where Indian history, relevant for our purpose begins. So if our idea of Secularism comes with the Constitution, that of Gender Equality and where necessary of Gender Neutrality or Non-Discrimination, too comes from the Constitution. By linear logic, if we believe in the Indian Constitution as our guiding principle, then we need to rethink the idea of the ‘Bharat Mata’.

Finally, by calling Bharat ‘Bharat Mata’, we somehow think we have done what needs to be done for the women in the country. In other words, the rhetoric around the word ‘Mata’, and the trait of being satisfied with symbolism means that we think precious little about doing something tangible and significant to improve the lot of women. Not just that, the larger communicable disease of paying lip service deadens our collective spirit and the need to do engage in deeper questioning of both – the systemic and individual discrimination that we witness everyday.

Recently, on a field trip on Mendha Lekha village in Mahrashtra, which is a village with largely tribal population, popularly known for their collective form of decision making with the village motto – ‘In Delhi and Mumbai, we have our Government but in our village, we are the Government’, the headman of the village remarked – “For us, those who consider ourselves as guardians of the forests, engaging in any type of agriculture was like using the plough on the stomach of our motherland!”.

(Picture of Mendha Lekha’s slogan : From Author’s Diary)

Ofcourse, this attitude has softened over the years and they do engage in agriculture now, but they still have that awareness around what it could mean to do or not to do to one’s ‘motherland’. This may be an extreme example. But let’s think of more everyday ones – those sprinkled all around us. How are we okay with sexist jokes, wife jokes, sexist words for which there is no male equivalent (‘rakhel’ or ‘keep’ for instance), sexist songs which reduce women to objects – which we defend in the name of entertainment, sexist advertisements which we defend in the name of commercialisation; sexist behaviour such as non transfer of equal property to women inspite of there being a clear law for it – in the name of culture? How are we okay when we don’t see women in public spaces – not in garden, in sports ground, out of homes after evening hours? How are we okay with deafening silence of women in our private spaces, where women hardly have space to express their opinion? How are we okay when someone we knows character assasinates another woman in a powerful position, just because it is easy to drag her down by talking of her character?

And no, it’s not just about men discriminating against women, but women discriminating against their own gender too. And why identify ‘Bharat’ with a gender at all – isn’t there space for those who have fluid gender too? Don’t we also see discrimination against men in our society? Don’t we have societies in India, which are women centric, sometimes leading to reverse discrimination against men?

So it boils down to this. Where does our need for identifying our nation with a gender come from. I will argue, that assuming the best, even if the intent of its origin is well placed, there exists no purpose beyond empty slogans, repeated ad nauseum to keep the collective energy high in all political gatherings, and now increasingly to suit vested political agendas.

Whether it is BJP’s – Bharat Mata Ki Jai or Congress’s Sevadal’s – Bolo Bharat Mata Ki, Jai, Jai, Jai – everytime we sing out this slogan, we need to pause, and ponder – are we doing enough for women, are we doing enough for all humans, for all living beings around it? Any politics which is based on ‘humanism’, cannot stop at the slogan of women, it has to constantly work tirelessly towards emanicipation of women.

While cultural expression of ‘motherland’ definitely got a boost in popular imagination with movies such as ‘Mother-India’, the political expression of it is worthy of taking note.

Interestingly, the image of Bharat Mata that is used by the RSS and BJP to depict a Hindu Goddess, was born out of angst against the Britishers’ Divide & Rule Policy implemented first through the Partition of Bengal – mainly Hindu West from the majority Muslim East.

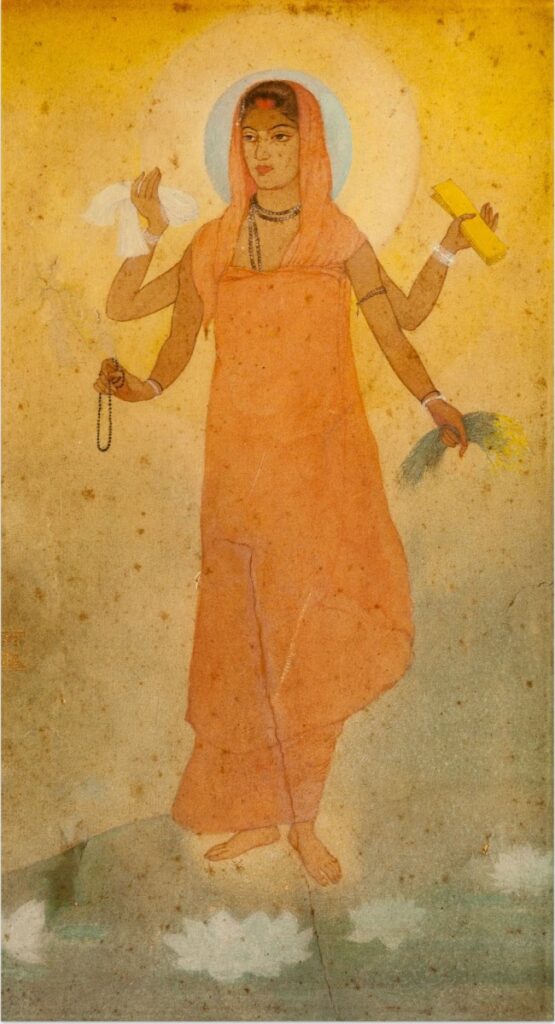

Abanindranath Tagore, decided to use Art to reclaim Indian heritage, painted – ‘Bharat Mata’, drawing upon the Japanese painter – Okakura Kakuzo.

(Image of Abanindranath Tagore’s first depiction of Bharat Mata)

This painting of Bharat Mata, was not to depict her as some Hindu Goddess, what one may perceive and RSS will have us believe looking at her saffron robe but as a pastoral deity holding ‘the four gifts of the motherland’: a white cloth, a book, a sheaf of paddy, and prayer beads; representing clothing, learning, food, and spiritual salvation. These symbols of Indian motherhood, which held emotive substance for Hindus and Muslims alike, are key to Tagore’s aim of conceptualising a ‘spiritual’ identity for his people, in direct contrast with the perceived ‘materialism’ of Europe.’

Then came Bankimchandra Chattopadhyaya’s ‘Anand Math’ which celebrated India as a motherland -as a goddess, thereby taking this idea deeper into the imaginations of the masses. But while both Tagore and Chattopadhyaya’s idea of Bharat Mata came from a nationalistic fervour, it was the RSS which added the ‘Hindu Goddess’ tint to it. With RSS pushing the wall, with installment of Bharat Mata statue at RSS office, in Bareilly, UP, as latest as yesterday, it is now anyone’s guess, what a Bharat Mata holding a saffron flag is meant to depict – Hindu Nationalism – an idea that works for the RSS and BJP but an idea that is simply against the idea of the Constitution and the idea of India that emanates from it.

(RSS’s Picture of Bharat Mata)

Therefore it’s important to remember that those who championed the idea of Bharat Mata earlier, did so, because its origins were in ‘inclusive nationalism’ – that stresses on the emotions of seeing and treating one’s nation as a motherland, according women the highest respect in words and in action, and definitely a mother – who is a mother for all – a mother who doesn’t discriminate between her Hindu daughter and Muslim daugther.

One illustration of this is in Nehru ji’s own words who asked the people he met – “Who is this Bharat Mata, whose victory you wish?”, and then explaining that said “the mountains and rivers, forests and fields are of course dear to everyone” but what counted ultimately “is the people of India…”.

RSS, is now reversing this very idea of India and also that of Bharat Mata. While exalting Bharat Mata and installing her statute in different RSS offices, they are striking at the root of its origins – a Bharat for all, where all are treated with a mother’s love. As a people, we need to see RSS’s way of appropriating symbols and using them to serve their own political agendas, which is in sharp contrast with what that symbol originally represented – with the spirit of the Indian Constitution.

So everytime we use the expression ‘Bharat Mata’ now, we need to rethink and think deeper. We need to install Constitution in the hearts of the people, and make ‘the people’ realise that it us who are ‘Bharat Mata’. Bharat, thy name is enough.

Victory to the People, who have given this Constitution to ourselves. Yes, yes, we are the Bharat! And what we need, for a statute loving country that we are, unwilling to compromise on the politics of symbolism, which may have some purpose is a – Constitution in every square and circle of our country.

Avani Bansal is an Advocate and a Member of the Congress Party (Twitter @bansalavani).

This article was first published on The Wire

https://m.thewire.in/article/women/bharat-mata-india-women-respect-safety-discrimination/amp