By Dr. Elsa Lycias Joel

Kalaignar’s political ambitions have trickled down to the third generation for good.

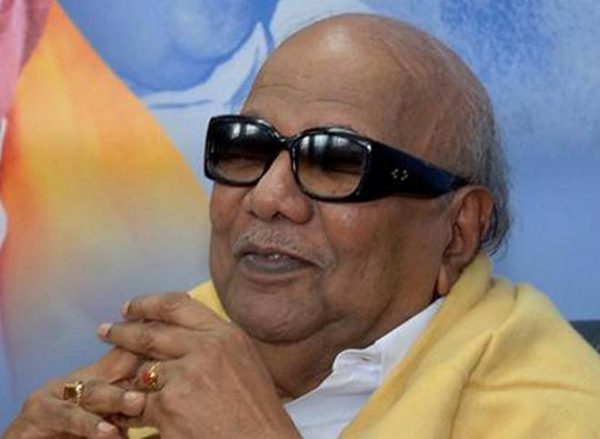

Tamil Nadu knows of Muthuvel Karunanidhi (popularly referred to as ‘Kalaignar’ – Artist), as a leader who established himself as a screenplay writer, scriptwriter, actor, writer and poet with more than 100 books to his credit, an enormous intellect of our times and above all elected as chief minister for five times. Dr. Karunanidhi, more than most others, knew what it’s like to come up the hard way.

In a sense Karunanidhi’s fame was first cemented with his participation in the anti-hindu agitations at the age of 14 followed by his maiden attempt as founder and editor of ‘Manavar Nesan’ (friend of students), a handwritten newspaper circulated among members. A penchant for classic literature motivated Dr. Karunanidhi, to write screen plays for five epics marked by a caustic wit and elegant script that demeaned primitive ideas that subjugated women in particular. Through his writings, this stalwart implored a change in public values in favour of supporting everything from arts and literature to better living for the poor, and he compelled the governments at the centre to pay heed. He had the guts to call the mother organization of the ruling party at the centre as a controversial organization based on religion.

Tamil Nadu celebrates this man, as he uniquely focused on the issues of Indian widow and untouchability, considered taboo topics, through his screenplays, thereby ushering in widespread social reforms. Thanks to him, Tamil Nadu does not any longer accept the custom of breaking of bangles by women on the death of their husbands, or dis-figuration and maltreatment of such women and does not accept any abuse of widows by conjoining the cultural, caste and property imperatives that were tolerated in this state of India, for so long.

Tamilians have reasons to be grateful for his life. DMK Patriarch renounced religion and fought religious patriarchy tooth and nail because it worked as a means to coerce women into accepting gender oppression through religion.Even after being reformed, Hindu personal laws denied women of co-guardianship rights over her children, right to ancestral property and wealth. Movies like ‘Panam’ and ‘Thangarethnam’ conveyed strong ideas of him as a screenwriter. In 1952 through the movie ‘parasakthi’ he vindicated illiteracy, early marriage, social inequality, casteism, social dependency and stigma of widowhood. In Tamil Nadu, Dr. Karunanidhi is still seen as greater than God by many. For countless, the fact that they can boast of a lifestyle that was earlier considered a prerogative of the rich and privileged, is a matter of considerable satisfaction and pride and they owe it to Dr. Karunanidhi.

To appreciate Dr. Karunanidhi’s role as champion of the oppressed, one needs to take a glance at the holy city of Vrindavan near Mathura and Varanasi. The sight of abandoned widows begging, in addition to tolerating the cruel slings of societal indifference is pathetic. Can a widower survive on a dole of a handful of rice and Rs.8/ day by singing bhajans? How widows are treated in our country is an open refutation of the belief that in our culture a mother occupies a higher position than anybody – Matru devo bhava, Guru dev bhava. These ostracized widows are living symbols of the failure of our already inadequate systems.

Not only was a woman’s legal protection within a family made true under the Tamil Nadu Marriages Act in 2009 but bearing the expenses of inter-caste marriages by the DMK was another move to weaken the casteist forces. The first big move that the DMK made under the leadership of Karunanidhi was to pass a law calling for the legalization of self-respect marriages in 1967, which is also reflective of the man’s premeditated attempt to banish religious hierarchy. This paved the way for Hindu marriages minus the presence of a Brahmin priest. Social reforms in the eyes of DMK chief centered on the secluded downtrodden people and widows. Social equality was DMK’s flagship. The two dozen and odd welfare boards set up during the DMK’s regime aimed at equality. Reservations and quotas created were so sensitive to the plight of the suffering lot who are segregated in other parts of India on the basis of the Dharmaśāstras of Hinduism. By introducing the Women Entrepreneurs scheme and Women’s Small Trade Loan with saving scheme, he ensured to promote social capital, equality and social justice.

As first among equals, he secured a precious right for all the Chief Ministers and on August 15, 1974, Mr. Karunanidhi became the first Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu to unfurl the national flag at the historic Fort St. George. The highest point of his “avatar” as a proponent of the Tamil language was marked by the Union government’s declaration of Tamil as a classical language in October 2004. The idea of State autonomy was perceived by him and it still flourishes for the good of all the State governments, and not to any particular party.

With such a strong leader as Dr. Karunanidhi, whose focus was also on demolishing the caste hegemony over society, it remains to be seen if other states have understood Tamil Nadu’s political dynamics. In whatever he did, there was a sense of social justice. Kalaignar’s atheism never conflicted with his ideology and he stood by his credo, that, discriminating against fellow beings in the name of religion and caste is inhuman. There are no questions or doubts as to how he presented himself as the savior of the oppressed and downtrodden and how he set a precedent for the future.

Twelve years after the Tamil Nadu government’s order, a person belonging to the so called non-creamy layer was posted as ‘Archaka’ at the famous Meenakshi Amman temple in Madurai. The war has just begun and Dr. Karunanidh’s legacy will live on.

“May every sunrise hold more promises “