By Kokila Bhattacharya

I started writing this is in disbelief, and exhausting rage, which quickly extinguished into helplessness, and permeated as grief and eventually settled down as our default state of being — despair. But despair doesn’t warrant change, so I’m writing to you, in hope. Hope that doesn’t exist in this burning world, but is created, over and over again. And even though I am yet to witness this personally — I want to believe that you, our integrity to change and respond with accountability and our blueprint for the future can sit here together.

If you’re a cis het man and feeling a bit helpless, anguished, angry and even defensive — you’re at the right place.

(TW: persistent mention of sexual violence) (scroll to the end for “the point”)

On Anger and selective rage

OURS :

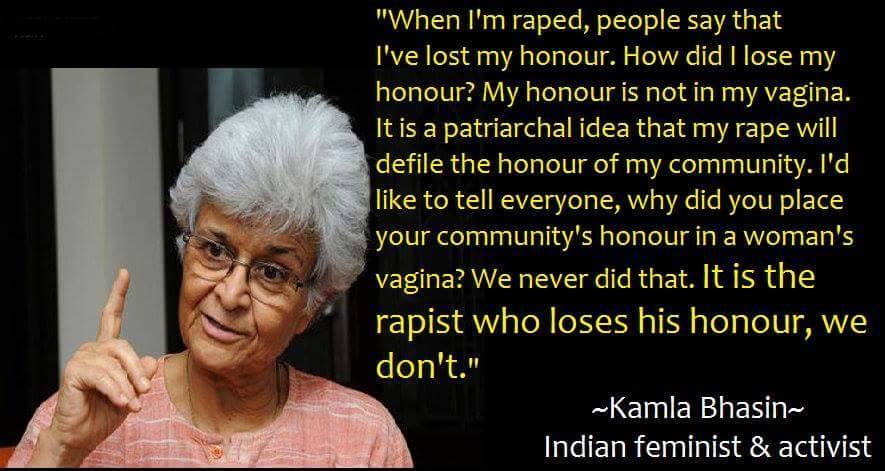

This is not about you. Inside our anger lies a deep sense of betrayal of our boundaries and autonomy from the moment of our birth. It often turns into grief because, despite the continuous injustices we face, no one truly listens. You may trigger or provoke this anger, but it’s not about you personally — it’s about what you have come to represent. Our anger is sacred and generational, growing with each episode of injustice, rooted in our collective experiences and solidarity. We are accustomed to our experiences being invalidated and our anger dismissed as an overreaction. Let my anger, our collective rage, be about that.

YOURS :

If you feel discomfort or defensiveness, it’s an invitation to begin understanding the intensity of what many experience on a daily basis. There is a larger systemic problem that hurts you as well. This write up is obviously propelled by the (outrage at) heinous violence at RG Kar. However, at the risk of meddling in whataboutery, I’d like to examine our collective reactionary bouts. After all, its 22 years since Gujarat, 12 since December 16, 4 since Hathras and not even a second since the last act of violence by a man.

- When you feel anger about the violence at RG Kar, what exactly are you reacting to? Besides death, what parts of this kind of violence makes it ‘heinous’ ?

- Are you outraged because the victim shares certain identities with you? How might that shape your response?

- Would your empathy and sense of justice be the same if the survivor were male, a trans person, or a sex worker? A bahujan homemaker, a muslim farmer; would your anger be just as intense?

- How did you respond to the news of the dalit minor whose life was taken by sexual violence in the same week? Did it evoke the same level of outrage?

- Are there any underlying biases or societal influences shaping the strength or direction of your anger?

On the nature of Rape

Rape is a tool — a political one. By defining politics as the exercise of power, rape becomes an instrument of power. It’s rarely driven by sexual desire but often by hatred, which can be cultivated and manipulated. This makes rape a political tool, used in warfare and to settle scores. Like any violent act, understanding the politics of rape requires understanding the politics of violence across caste, communal, economic, and gendered contexts. It is to dehumanize— a blazing statement to anyone taking space, “How dare you?”

It is not merely the lack of consent. If sex is about pleasure, rape is designed to inflict pain.

In a country where nothing and nobody moves until the politician does, why only have this exception about not politicising rape? Asks Rama Lakshmi

I find it pertinent to note that unlike above, the “politicization” of rape is, different, the latter being the conniving exploitation of an issue for political gains, (like we witnessed post Kathua) and choosing some over others as electoral agendas. As stories from Dalitbahujan women, muslim women and wmen from Manipur will tell you, the system has not just failed us but enabled perpetrators over and over. And women’s lives and their bodies have been the unacknowledged casualties of war for too long.

A few examples:

- Rape as a tool of war is not new in Manipur.

- The Womb as a Weapon in Palestine.

- Soldiers and police use rape as a weapon: to punish, intimidate, coerce, humiliate and degrade in Kashmir

- Extremists have a pronounced ideological warfare against values such as gender equality, which makes women more vulnerable.Sexual violence has been used as ameans of ethnic cleansing in Iraq, Bosnia, Rwanda, East Timor, Sudan, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Burundi, Jordan, Syria, Ukraine, and Colombia.

Patriarchy x Caste

Both are rooted in a shared desire to assert dominance and control, with sexual violence often being used as a deliberate tool to reinforce caste-based oppression. Just as caste determines social status and access to resources, it also dictates who holds power over others, perpetuating a system where violence, including rape, is wielded to maintain and enforce these hierarchical boundaries. Savarna men, at the top of this hierarchy, benefit the most and often operate with impunity.

It’s illuminating that NCRB’s data reveals there was a 45% increase in reported rapes of Dalit women between 2015 and 2020. The increasing incidences of gender-based violence (GBV) against lowered-caste women prove that we fundamentally undermine their social, economic, political, and cultural rights.

Patriarchy x Nationalism ( ≠ patriotism)

When a hyper-masculine country believes it is greater than anything else, nationalism becomes a force that valorizes strength, creates enemies, and shields perpetrators of violence. This belief system, intertwined with the invocation of religion and cultural purity, turns rape into a tool for silencing dissent and asserting control. Much like caste and gender, which are rigidly defined by birth and upheld as a form of superiority, nationalism is often treated as an inherited virtue rather than something earned or truly virtuous. This narrow, inherited blindfold of “nationhood” is celebrated as a mark of superiority, obscuring the humanity of those outside its definition and perpetuating an environment where degradation and misogyny are normalized. Just as ‘Bharat Mata Ki Jai’ became a symbolic and pious deification, this narrative is also where Jyoti’s story was appropriated into “India’s daughter”, reinforcing nationalistic and patriarchal ideals rather than addressing the underlying issues of gender violence.

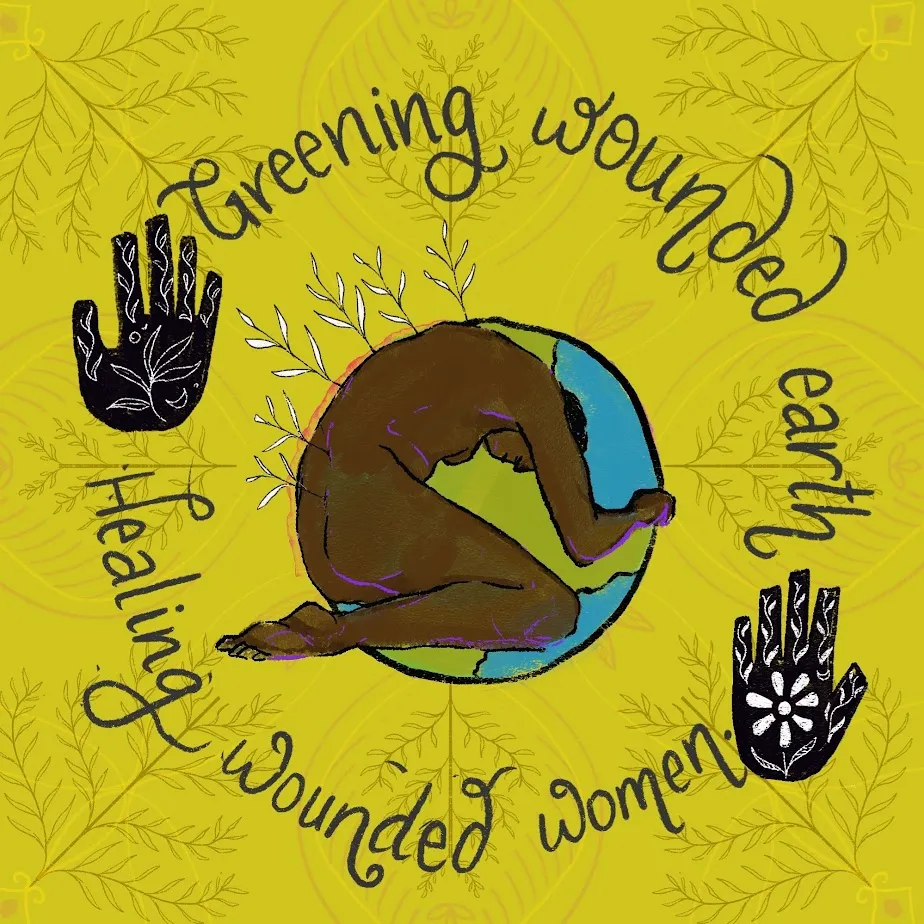

Capitalism x Patriarchy

It is no surprise that gendered violence and ecological destruction go hand in hand. Capitalism prioritizes competition, dominance, and the commodification of resources, fosters a culture where power imbalances are normalized and exploitation is justified. This mindset reduces people and their bodies to commodities, fueling a sense of entitlement that contributes to rape culture, where women’s bodies are seen as objects to control rather than autonomous beings deserving of respect. By dehumanizing individuals and prioritizing profit over empathy, capitalism nurtures the conditions in which rape culture thrives, mirroring the exploitation of natural resources with the exploitation of vulnerable populations.

Examples like exploitation and bonded labour in Tamil Nadu’s textile mills and rampant harassment at companies like TCS are just a few byproducts of this production frenzied. Marginalized communities face the greatest risks.

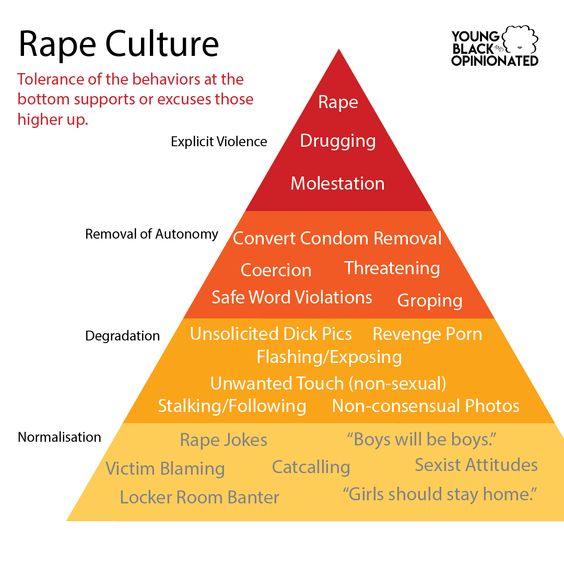

What is Rape Culture?

It is the stinking environment we live and breathe — a culture where sexual violence is normalized and even glamorized. Misogyny isn’t just present but actively perpetuated, feeding into a system of rampant objectification and systemic degradation. This culture is both deliberate and structural.

The hyper-masculine nature of movements like Hindu supremacism mirrors global alt-right trends, where violence disproportionately targets women, especially those from marginalized communities. This toxic masculinity, often intertwined with nationalism, normalizes sexual violence as a tool of power and control. Rape culture thrives in environments where patriarchy and autocracy coexist, making it crucial to understand how these dynamics shape and perpetuate systemic violence against women.

While violence itself isn’t inherently gendered, the vast majority of it is committed by men, and patriarchy benefits from this reality. As a man, be cautious of right-wing narratives, particularly those with religious or mythological undertones. These narratives often confine women to roles where their honor or dignity is at stake, thus allowing men to assert their valor by “protecting” it. This dynamic only reinforces patriarchy and demonizes certain castes. We’re now at a point where a victim’s trauma is turned into a source of illicit pleasure for the public, an even distorted schadenfreude. This phenomenon is part of a troubling trend where violence is sensationalized and even eroticized, underscoring how deeply ingrained and exploitative these cultural dynamics can be. Ultimately, a ‘culture’ shapes behavior.

We don’t need your protection. We need you to be decent human beings.

Rape is Consensual: Inside Haryana’s Rape Culture | Documentary by The Quint | India’s rape culture: the survivors’ stories

On Masculinity

I’m nobody to define what it’s like to be a man. Even on days when I envy your perceived freedom, I wouldn’t trade my compassion for conflict. We’re all at odds with the patriarchy but men* embody it in ways I cannot entirely fathom. Often, it’s difficult to see when aggression has crossed into toxicity, because alpha male tropes are so normalized, especially in far-right narratives. As a country hinging towards the pious hyper-masculinism, we must question at what point religion became the creator of violence.

If gender is learned what can one ask oneself as a man to unlearn toxic masculinity

- What does it mean to be a man for me?

- What parts of this answer were actually perpetuated by the society growing up?

- What parts do I want to inculcate, which parts do I wish to unlearn, for myself?

- Post the #metoo movement — What has changed for me? Inside me?

Encouraging Healthy Expressions Of Masculinity To Prevent Rape Culture In India

On the idea of Justice

Judicially, there are four ‘theories of punishment’ ;

the deterrent theory which seeks to prevent future crimes by making severe examples of offenders and has had little impact on crime rates, the preventive theory which aims to stop reoffending by imprisoning criminals, but can lead to hardened behavior rather than rehabilitation, the retributive theory focusing on punishing offenders in proportion to their crime (like the death penalty in the Nirbhaya case). the theory of compensation which seeks to financially and morally compensate victims, but can oversimplify the complexities of crime and victim impact and the reformative theory rehabilitates offenders to reintegrate them into society, though it requires significant resources and may not work for all individuals.

Can the justice system, itself an extension of the patriarchal framework even offer solutions beyond this cycle of violence? In a country where rapists aren’t just let free but celebrated, garlanded in pomposity, survivors are dismissed, disbelieved, and left mentally undone, and legal processes remain inaccessible, what does justice truly mean? It is no wonder that 90% of rapes go unreported because the system is meant to re-traumatize. Here retributive justice feels like mere vengeance, running around in the perpetual cycle where violence begets violence.

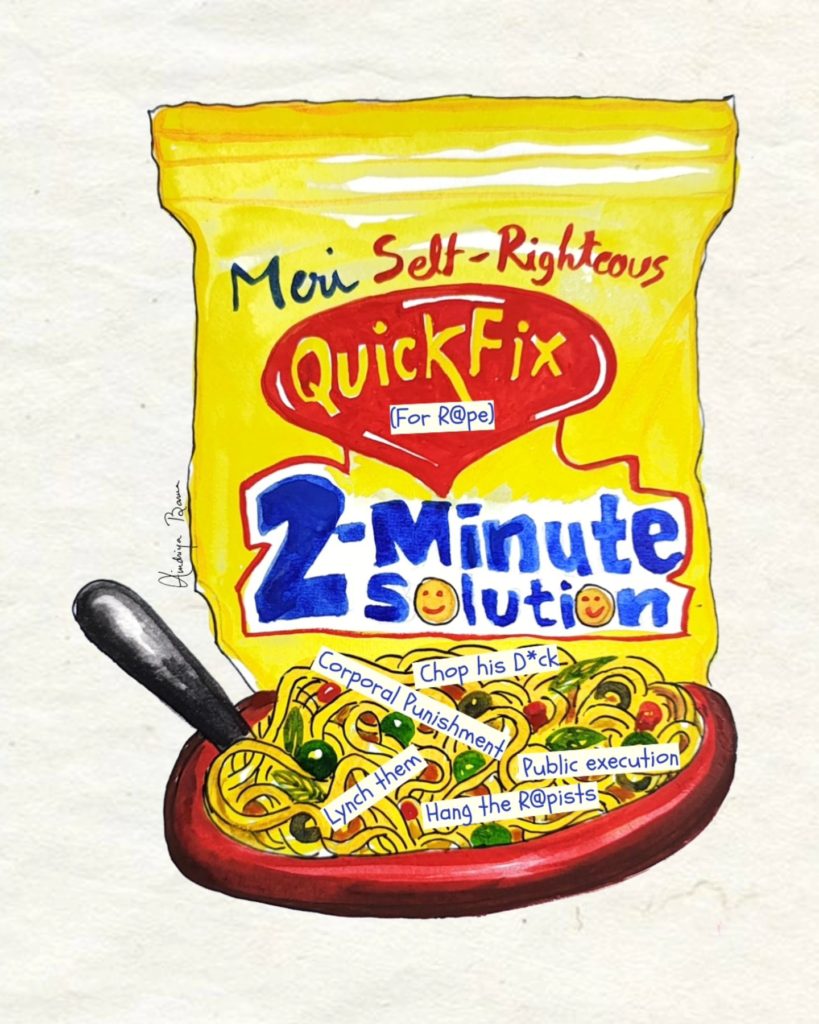

Mob violence and lynchings mirror this issue under the garb of taking the law into their own hands. Often viewed as a democratic response, is frenzied, unconstitutional, and non-reparative. Its immediacy and spectacle offer a false sense of gratification, frequently reinforcing biases rather than addressing underlying systemic issues. Is this ‘poetic’ justice, or just another form of oppression?

Now, as these systems fail, for survivors of sexual violence, and anyone having witnessed violation of their bodily autonomy, what is justice?

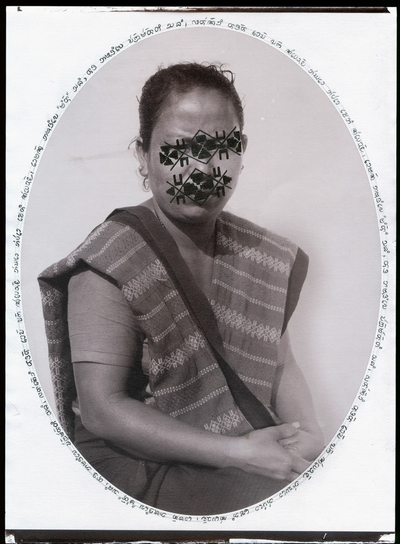

Can justice be about healing, even from the confines of traditional expectations of what this crime is supposed to do to me? Can we decenter rape from its stigmatized and sensationalized position as the ultimate violation against women. To effectively respond, we have to re-imagine justice. It needs to transgress beyond the punitive into restorative. It needs to become survivor led and centered, incorporating lived experiences into the process. It needs to recognize that each survivor’s experience and needs are unique and solutions cannot be straitjacketed. A sense of justice that involves the perpetrator’s accountability and the survivor’s recovery; a justice that isalso embodied, possibly even somatic.

A friend reminded me as I was recovering from a trigger meltdown, “If trauma shames and isolates, then recovery must take place in community”.

One Future Collective has many fantastic resources exploring justice, especially for supporting GBV survivors.

The perfect victim

We’ve all experienced that even in the most supposedly progressive places, women are supposed to become worthy of justice. Solidarity becomes conditional, subject to various `facets of our identities, whereabouts, promiscuity, because ‘respectable’ Indian women do not get raped. So it is of no surprise that atleast 40,000 of us aren’t respectable.

“میںسچکہوںگیمگرپھربھیہارجاؤںگی،وہجھوٹبولےگااورلاجوابکردےگا۔”

(मैंसचकहूँगीमगरफिरभीहारजाऊँगी, वोझूटबोलेगाऔरला–जवाबकरदेगा)—Parveen Shakir

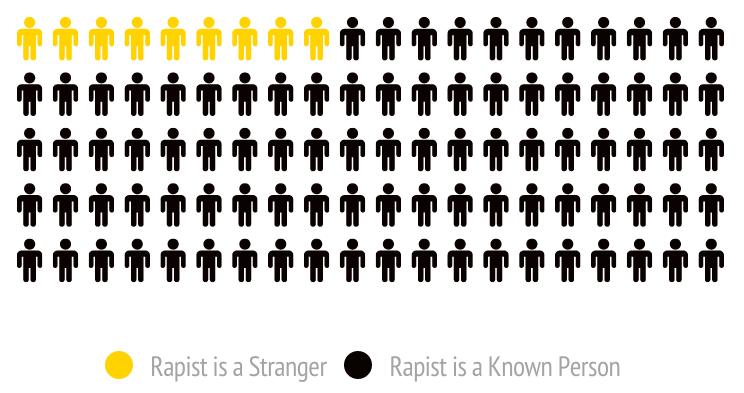

Tropes like ‘Bharat Mata,’ ‘Nirbhaya,’ and ‘Abhaya’, calling us sisters and mothers only reinforce this narrative, catering to those who consume victimhood for sympathy. The ideal victim is portrayed as chaste (either a ‘virgin’ or married), attacked by a stranger, resisting her attacker, and suffering severe injury or death.

Moreover, rape laws are far from gender-neutral. They are not friendly but rather patriarchal, reflecting a system where men’s experiences of coercion are either minimized or dismissed even as pleasure, and where they face threats without adequate protection.

India’s New Criminal Law Offers Little Protection Against Sexual Assault To Men & Trans Men | Kartikeya Bahadur & Sumati Thusoo

To truly move forward and address injustice, acknowledge that rape victims/ survivors are imperfect. They’re human.

The Demonised Rapist

The perils of stereotype do not limit itself to our idea of a rapist just because these are brutal crimes. In fact, by avanlanching the distance between ‘society’ (achha aadmi) and sexual assaulters, we ignore that these perpetrators are not anomalies but products of systemic design. If an assaulter were truly an isolated anomaly, there wouldn’t be over 3,000 searches for the victim’s name on porn sites, like vultures picking at ruins.

Deterrence or reform is unlikely unless we understand where this violence takes root. Such binary views vilify perpetrators and undermine the possibility of achieving justice or taking responsibility.

These may help to understand : Muskan Garg | Rape Mindset — Psychology Behind Sexual Violence // Kamala Thiagarajan | In Interviews With 122 Rapists, Student Pursues Not-So-Simple Question: Why?

(More on) Capital Punishment :

Knee jerk reactions like these do not offer solace to the survivor, but absolves us all of collective responsibility and accountability towards both cure and prevention. In its discomfort to face the perpetrator as the mere byproduct of a system, it wants to shove it away as garbage — loin des yeux, loin du cœur (out of sight, out of mind) — and pretend the underlying problem is solved. We will soon find out, as many feminists know, that the stench catches up sooner or later. If we are to really look at a person not devoid of his humanity, we must peer into the society that created him and acknowledge that a person is inseparable from his surroundings.

To point out the irony,

if rape is about power & control,

and the death penalty (supposedly) punishes you for

the ultimate heinous crime,

is it not a perverse reward to a rapist?

If not, this perspective certainly reinforces the idea that a woman’s worth is tied to her victimization, defined by their suffering rather than their agency, contributions, or rights, which is a tall patriarchal assumption.

To well meaning men around me, including my father, who staunchly believe a rapist should be hanged, I want to ask if they would advocate equivocally given the perpetrator is their brother, cousin, best friend, OR is all our demonizing limited to other (/othering of) men? And are we all ready to receive the punitive damages for creating and nurturing this ever growing macho aggression? Instead of focusing on revenge, we could invest in prevention, support, and systemic change to truly confront the violence at its core.

Let patriarchy be the only casualty.

Sahana Manjesh rightly elucidates here, ‘Why The Death Penalty Is Not A Solution To India’s Rape Problem’

West Bengal’s new ‘Aparajita Woman and Child Bill 2024

A Checklist

In my early teens, a listicle on how not to get raped stayed pinned to my cupboard. It took years for me to see just how regressive it was, but by then the work was done. It drilled into me a relentless hyper-vigilance, a suffocating belief that my safety was solely my responsibility, that if I was attacked or raped, it would be my fault. As women, we carry this list in various forms, etched into our very bones — always on alert, never safe, never calm. Betrayed nevertheless.

Here’s a list for you, of questions you can ask yourself instead.

As a human being

Personally :

- Have I fully owned and acknowledged my past actions or abusive behaviors, and am I committed to genuine repair?

- In what ways can I address and repair the harm I’ve caused, both to myself and others?

- How do I handle my own experiences of being abused, and am I actively working towards healing and not perpetuating the cycle?

- Am I engaging in actions that contribute to a culture of silence or complicity, and how can I actively oppose these patterns?

- How do substances like alcohol affect my behavior, and what steps am I taking to ensure I remain accountable?

- When you witness harassment, do you take action to support the victim or confront the perpetrator, or do you remain passive?

It’s harrowing to reckon with having been abusive in the past, but the only thing worse is never acknowledging it. Even though a bit redundant, here is the Attitudes Towards Women Scale test.

If you are struggling with trauma, Mithra Trust has a freshly baked beautiful resource : A guide to Understanding Trauma

Interpersonally :

As a Partner——I want to unashamedly start by stating that around 30% of violence against women in India is perpetrated by intimate partners. I have personally witnessed it more than once. What does the deplorable legality of marital rape in India reveal how we view ‘partnerships’?

Relationships or kinships are often the first place where childhood wounds get excoriated, both triggered and caused. Pleasure, love, and affection are the body’s ways of understanding safety. By failing to provide our partners with a sense of safety, we are saying that to be violated is a norm rather than an aberration. Cascading betrayals. You and your partner could ask yourselves :

- Do I understand non verbal cues of a no? Do I take no as a complete answer?

- Do I understand boundaries and what they look like when drawn?

- Do I understand the power dynamics in our relationship and how they might influence consent?

- What steps am I taking to address and heal my own toxic behaviors and patterns?

Why we don’t get consent by Paromita Vohra

( More : How Men Can Help Women Recover from Sexual Violence )

As a Parent

If your child lashes out at you for not protecting them enough, please see it as a sign of possible past harm. They are not necessarily blaming you, they saw you as their protectors. I hope you can take this opportunity, even in retrospect, to let them know you believe them and stand up for them (especially if there’s an abuser in the family)

Most of us did not have that privilege.

Further, as a father, you may ask yourself

- How am I teaching my children about consent, respect, and healthy boundaries to prevent sexual abuse?

- How am I, as a model, actively challenging and changing any harmful attitudes or behaviors I might have inherited or witnessed?

Here are helpful resources from Protsahan India Foundation : How to talk to your kids about child sexual abuse and rape .

As Friends / Active listeners / First Personal Responders —

When I’ve shared my experiences of abuse with male friends, their responses — ranging from wanting to react violently, showing disgust, prying for more details, blaming me, or offering superficial apologies — have been unhelpful. I know this is just my experience, but I’ve regretted confiding in them.

- How can I listen supportively without reacting with disgust or blame?

- How can I create a safe and empathetic space for survivors to share their experiences?

- How can I challenge and change harmful attitudes about sexual violence in my circles?

- Have I already taken the step to unfriend or distance myself from those who are rapists or abusers, given that they have not changed?

If you are a feminist, you will be a perpetual killjoy.

Here are a few questions you can ask yourself if you belong in these spaces

Tech Sector

- In what ways are you ensuring that your data collection and research practices are equitable and reflective of diverse experiences, especially those of marginalized women?

- Is your intervention aka product focused on making women’s lives safer through gadgets, or is it addressing the root causes and holding perpetrators accountable by shifting the responsibility from women to those who commit violence?

When our bodies are war zones, pepper sprays aren’t designed to scare away the patriarchy and a safety ‘hack’ is the last thing we need.

The Arts

Art is political — stop pretending it’s not. Women are being molested at mosh pits, by classical gurus, and even by supposedly progressive writers, designers, comedians. Our beliefs must transcend the content we create and become the lives we lead.

Sameera Iyengar says, “It is the role of the arts to ask the hard questions, to understand the world through emotion and experience, to propose other ways of being”. She asks How do we collectively create a world of theatre where women feel safe and respected?

- Does your work challenge harmful stereotypes and promote respect?

- Are your actions and public stances aligned with the values you promote in your art?

- What initiatives are you supporting or leading to create safer environments in Indian art spaces where women and marginalized artists can thrive without fear?

Films as maker and viewer

- What steps are you taking to create a safe and respectful environment on your sets, and how do you ensure that your films do not glamorize or trivialize violence against women?

- In what ways do you support and seek out films that offer respectful and nuanced representations of women’s experiences in India?

- How do you respond to problematic content in popular films — do you challenge it, discuss it, or dismiss it as mere entertainment?

A movement is brewing within the Malayalam & Tamil film industry thanks to the courageous women rising against the rotten system of Kerala. I am looking forward to your amplification of it.

Health Sector

The body stores trauma at a primal level. Aruna Shanbaug, who was failed by the system time and again gave us the gift of escaping this body’s entrapment. Despite her vegetative state, it is documented that Aruna would react violently if she heard a strange male voice.

Gabor Maté, renowned physician, argues alongside Dr. Bessel van der Kolk, an expert on trauma, that “the body keeps the score,” and this storage can manifest as physical symptoms, chronic stress, and various health issues.

- Are you advocating for trauma-informed care that acknowledges the long-term effects of abuse, or is your focus limited to immediate medical needs?

- Do your practices and policies address the chronic pain and PTSD that many survivors endure?

Socio-Developmental Sector

- Are you integrating gender equality into every aspect of your projects, or is feminism treated as a peripheral concern?

- Are your initiatives designed to drive systemic change rather than offering token gestures?

- How is your organization ensuring that its Internal Committee (IC) is compliant with the POSH Act, with a diverse and well-trained team capable of handling cases with sensitivity and urgency?

- Additionally, what specific measures have you put in place following recent amendments to the POSH Act to make sure survivors feel safe and supported when coming forward, especially in cases involving senior or influential members?

Education

- Are you teaching boys about consent and respect from an early age?

- Are your educational programs comprehensive and inclusive, or do they fall short of addressing the complexities of gender dynamics?

- Is your school curriculum periodically audited to ensure that they eliminate the scope of perpetuating prejudice, stereotyping and patriarchy?

Politics

- What concrete steps are you taking to introduce or support legislation that provides comprehensive support for survivors of sexual violence, especially those from marginalized communities, while also ensuring that politicians accused of such crimes are held accountable?

- How are you actively advocating for the reform of training and procedures within law enforcement and the judicial system to ensure that cases of sexual violence involving politicians are handled swiftly, impartially, and with a deep understanding of intersectional issues?

- What initiatives are you leading to promote transparency, accountability, and survivor-centered approaches within the political sphere, particularly in collaboration with civil society organizations, to ensure that all survivors receive the support they need and that accused individuals are held responsible?

Avani Bansal and Kanksshi Agarwal urge us to introspect Charity Begins at Home: Political Parties Must Lead the Way to Make Working Spaces Safe for Women

Workplace

- How are you implementing evidence-based strategies to create a safer and more inclusive workplace while actively challenging harmful informal conversations among peers that perpetuate a toxic culture?

- How are you using research on gender dynamics and power imbalances to disrupt behaviors that silence women’s voices, and how are you standing with women who speak out against harassment in your organization?

- What steps are you taking, both professionally and personally, to ensure that anti-harassment policies are rigorously enforced and supported by a culture of accountability and respect for all voices?

Sports

- When confronted with the pervasive culture of power in sports federations, how are you actively challenging those who use their influence to protect abusers?

- What actions have you taken to ensure that women athletes in your care feel safe and supported, even when speaking out against powerful figures?

Social Media

Our indulgence at the salacious details of the victim’s injuries caused brings us to question where rape culture ends and distorted consumption begins.

- How does your advocacy against sexual violence on social media align with your behavior in private conversations and relationships?

- When you encounter content that trivializes or sensationalizes sexual violence, how do you actively challenge it, both online and in your personal interactions?

- How do you navigate engaging with the work of individuals accused of abuse, and what actions do you take to address cyber sexual bullying or misogyny, ensuring you’re not leaving the labor to others?

Media

“An extension of this is the fact that in this culture, to be socially obtrusive, an incident of rape needs to provide some rasa to the ‘consumer’—bībhatsa, bhayānaka or karuna, to be consumed and derived the respective values from. These emotions are not just organic reactions but are rather deliberately cultivated to create a consumable narrative that caters to a voyeuristic audience.” write Sagrika Rajora and Aditya Krishna.

- How often do you critically evaluate the impact of the stories you choose to cover, ensuring they do not perpetuate harmful stereotypes or sensationalize sexual violence for shock value?

- Are you demanding better representation and respectful portrayals of women, rather than allowing harmful stereotypes to persist?

- In what ways are you actively challenging and transforming existing narratives within media to promote respectful and sensitive representation of survivors of sexual violence?

- Are you supporting feminist grassroot media outlets that fosters positive and respectful narratives?

Law

- Are you actively ensuring that your legal practice is sensitive to the needs of survivors and inclusive of LGBTQIA+ individuals?

- How are you confronting and changing the systemic misogyny and indifference present in legal procedures?

- What immediate actions are you taking to advocate for gender-neutral rape laws? How are you applying insights on dismantling rape culture to drive meaningful change in legal protections and support equitable reforms?

Creation of Alternate Systems

Every act of violence is an opportunity for us to recreate the systems we operate in. When we are fraught from fighting systems, dismantling hierarchies and and the dust of the ruins envelope us (an everyday gathering), what do we make?

What kind of culture do we want to embody, instead? What can our children learn here of freedom and what would it take for us to live through ecologies that are casteless, egalitarian, equitable, inclusive, compassionate? How can we enable each other to become ourselves in our wholeness? Can we relearn the craft of repair and healing, mending and fostering healthy, sustainable relationships with ourselves, each other and the system?

As Nora Samaran writes,

“violence is nurturance turned backwards.”

In its place, she proposes “nurturance culture” as the opposite of rape culture, suggesting that models of care and accountability — different from “call-outs” rooted in the politics of guilt — can move toward dismantling systems of dominance and oppression.

For everyone catharsis means a different ideal. To forge a future rooted in justice, we must begin to actively dismantle hierarchies that perpetuate caste, class, and gender oppression now. This means creating systems that prioritize the dignity and liberation of the most marginalized, ensuring our structures support genuine social justice. We must decentralize power, with relationships and governance built on cooperation, mutual aid, and accountability.

May our focus be on fostering environments where respect, compassion, and connection are central. By repairing broken ties to ourselves, each other, and the Earth, we can build communities that truly value and support everyone. In doing so, we lay the groundwork for a future where justice and care are the driving forces in our collective lives.

I don’t know if I believe in the future carrying catharsis or healing for us. But I hope you do.

First Published Here: https://medium.com/@KokilaB/so-what-can-men-do-ffe8917c9154