By Pooja Bhattacharjee

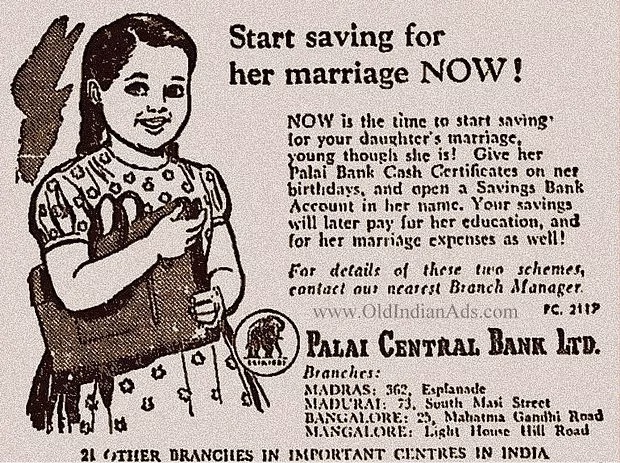

Advertisements have been an important medium for companies to promote their products through powerful messaging. Thus many companies try to come up with unique taglines or innovative ideas that people associate with their brand products. Marketing in India has become increasingly focused on gender roles, family hierarchy, and traditional marriage practices. Companies usually resort to ad campaigns which have a major issue of objectification and stereotyping women. In the process of attracting attention to aid recall, advertisers often resort to sexual themes. Evidently, such themes demand the presence of attractive women and explicit plots. These themes often lead to portrayals of a particular gender (mostly women) in a derogatory fashion.

When we act out our roles in everyday life, we internalize received information on our identity in the form of social “scripts” that we repeat and perfect over time. Popular culture often provides striking examples of such gendered scripts, as evident from studies on television and advertising as well as in social media and music. Traditional scripts require rewriting to fit new and previously unimagined situations. The makers need to be conscious of what they are putting out in the public sphere, either way, even as an act of morality and responsibility towards the society. This is the right time to revisit the advertising culture in India over the years and studying its relevance in the 21st Century.

This Usha ad from 1980s has the tagline, ‘train’ her to be the ‘ideal housewife’. The idea behind the ad that all girls should be raised to be the ideal housewives is problematic since it doesn’t directly target women to buy their products, however, it’s speaking to the parents or the person who has authority over the girl to ‘train’ her to be ideal housewife by getting this product. This ad is highly misogynist in the sense that it’s setting a bar for women to be ‘ideal’, which shouldn’t have existed in the first place. Furthermore, the fact that this ad aired in the 1980s, the highly patriarchal era where women did not much autonomy, it can only be inferred how much added stress they might have to endure to be the ideal type. This and many other sexist ads which came out decades ago cannot be absolved of the liability just because it came out a long time ago. They did contribute to the set gender norms which we are still fighting today.

An analysis of Indian advertisements on television and YouTube has shown that while they are superior to global benchmarks, insofar as girls and women have parity of representation in terms of screen and speaking time, their portrayal is problematic and have misogynist roots, as they further gender stereotypes – women are more likely to be shown as married, less likely to be shown in paid occupation, and more likely to be depicted as caretakers and parents than male characters.

A study by UNICEF and the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media (GDI) titled “Gender Bias and Inclusion In Advertising In India” finds that female characters dominate screen time (59.7%) and speaking time (56.3%) in Indian ads, but one of the drivers of this is their depiction for selling cleaning supplies, food and beauty products to female consumers. For example, almost all the detergent and food commercials depicted a woman caretaking for her family who speaks directly to women viewers about caring for their families. In comparison, in a separate study by GDI for setting global benchmarks it was found that ads in the U.S. show women with half the screen time (30.6%) and nearly half the speaking time (33.5%).

A few years ago, HUL was criticized for a misleading Vim bar ad. The ad video depicted the life of Afroz – who was the Pradhan and encouraged to stand for the elections by her husband as he felt that she was a better candidate for the post than him because she had studied more than him. The ad then shows clips of Afroz working and interacting with locals. Afroz tells us that she’s the Pradhan but she’s also a homemaker. The ad ends with a shot of her washing dishes with Vim soap. For few people, this ad may look innocent enough – a woman in power in a professional capacity comes home and does the domestic chores. Maybe this perception comes from the misogyny that we have internalized over the years – and the juxtaposition of women’s professional success with their efforts on the domestic front all the time.

There’s nothing wrong with washing dishes and the backlash that this ad got is not a criticism of Afroz or her husband. This is about how Vim appropriated this story and the way in which they chose to tell it. Making it palatable enough for those of us who cannot handle a woman’s success if she isn’t also simultaneously a domestic goddess.

The study shows that two-thirds of female characters (66.9%) in Indian ads have light or medium-light skin tones — a higher percentage than male characters (52.1%). Female characters are nine times more likely to be shown as “stunning/very attractive” than male characters (5.9% compared with 0.6%). Female characters are also invariably thin, but male characters appear with a variety of body sizes in Indian advertising.

A greater percentage of female characters is depicted as married than male characters (11.0% compared with 8.8%). Female characters are three times more likely to be depicted as parents than male characters (18.7% compared with 5.9%). While male characters are more likely to be shown making decisions about their future than female characters (7.3% compared with 4.8%), the latter are twice as likely to be shown making household decisions than male characters (4.9% compared with 2.0%). For characters where intelligence is part of their character in the ad, male characters are more likely to be shown as smart than female characters (32.2% compared to 26.2%). Male characters are almost twice as likely to be shown as funny than female characters (19.1% compared to 11.9%).

This unimpressionable ad of Jack & Jones released in 2016 shows a man objectifying women and letting them ‘hold him back’. The picture provides an apt summary of what the campaign is about. ‘Don’t hold back’, usually used as an empowering message is used here for a man to assert his power over a woman. Moreover, this ad seems to glorify sexual assault at work. Many ads objectify women by using them as ‘props’ in the ads- meaning that their presence limited to the background solely to provide a sexual appeal.

Airtel recently released an ad – it begins with a man sitting at the head of the table while his daughters, wife and mother are asking him to pay their bills. The man then looks at the camera and says it’s his duty to pay the bills since he’s the CEO of the house. Though this one didn’t gain as much criticism as the other ads, the subtle undertone of sexism does not go unnoticed. They all played a role in stereotyping the gender roles.

Misrepresentation and harmful stereotypes of women in advertising have a significant impact on women — and young girls — and how they view themselves and their value to society. While we do see female representation dominate in Indian ads, they are still marginalized by colorism, hyper-sexualization, and without careers or aspirations outside of the home,” said Geena Davis, Academy Award Winning Actor, Founder and Chair of the GDI adding that the stark inequality evident in portrayals of females in these advertisements must be addressed to ensure an equitable society.

Some ad campaigns are becoming increasingly aware of their presence in this industry. Social marketing has brought forth different forms of ‘femvertizing’– which is female empowerment through socially-focused marketing. This is done in a way that not only challenges but also reverses the traditionally dominant roles that Indian fathers, sons, and husbands assume with the women in their lives.

The ads of the detergent brand Ariel with tagline ‘share the load’ has been applauded for its inclusivity and helping in demystifying the pre-set gendered notions through this platform.

Also, more than a quarter of a century after Cadbury released its advertisement featuring model Shimona Rashi on the sidelines of a cricket match and zoomed past the security to celebrate with a dance on field when the cricketer – presumably her boyfriend – scored the winning run, Cadbury has reimagined this advertisement – changing very little except gender roles. This time it’s the same scene, expect it is a man on the sidelines and it’s a women’s match. Inter changing the gender in this advertisement also magnifies women’s achievements after the struggles women had to endure to reach this position.

Only time will tell which course the advertising sector will take. It is high time that the advertisement makers stop using satire while referring to women. Especially in this world where a new generation of feminist Indian marketers are using publicity to reach larger consumer audiences and to reframe the dominant gender discourse, recognizing the hugely important role that women play in global consumption.